In 2009, Olafur Eliasson began a series of circular paintings inspired by the idea of producing a new, comprehensive colour theory that would comprise all the visible colours of the prism. He began by working with a colour chemist to mix in paint an exact tone for each nanometre of light in the spectrum, which ranges in frequency from approximately 390 to 700 nanometres. Since those initial experiments, Eliasson has branched out to make a large number of painted works on circular canvases, known collectively as the colour experiments. A number of these works take their palettes from other sources, from historical paintings by J. M. W. Turner or Caspar David Friedrich, for example. In the case of ‘Colour experiment no. 108’, the muted tones in the background were derived from the colours found in a photograph taken by the artist in Iceland in 2012. A formless multicolored explosion spreads out from the centre of the canvas, contrasting starkly with the smooth, even background.

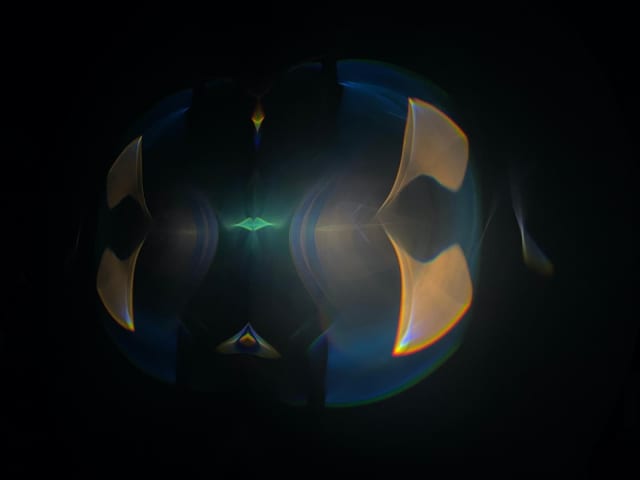

'The missing left brain', 2022. Now on view as part of Olafur Eliasson's solo exhibition 'Navegación situada' at Galería Elvira González, Madrid. Photo: CENIZA

'The missing left brain', 2022, unfurls before the viewer as a constantly changing lightshow of shapes, colours, and shadows, created through the reflection and refraction of light. The symmetrical sequence develops and vanishes in a slow continuum upon a circular screen that seems to hover in the space. The screen is in fact a semicircular screen affixed to a mirror, which creates the illusion of a full circle and doubles the amorphous shapes into a symmetrical Rorschach-like light display.

Viewers can glimpse the apparatus responsible for producing the projection inside a custom-made box mounted behind the screen. The box contains disparate glass lenses, colour-effect filters, and objects from Eliasson’s studio. A light inside the box illuminates the objects as they turn, and the resulting distortions are projected via a lens onto the screen. As each motor revolves at its own pace, the relationship between the various elements constantly changes, so that the light sequence appears always new. Chance alignments produce an ever-changing symphony of shadows and reflections on the screen – a phantasmagoria of evolving shapes, arboreal shadows, spectral arcs, and fields of colour that wax and wane and ooze across the surface of the screen.

'Colour experiment no. 94', 2020. Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Jens Ziehe

Several paintings in Olafur Eliasson's solo exhibition 'Your light spectrum and presence' – currently on view at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in Los Angeles – feature the bright spectrum of colour seen in the natural phenomenon of a rainbow, a recurring motif throughout Eliasson’s practice.

‘In the hurly-burly of everyday existence, the generosity of the rainbow lies in its unexpected appearance. It is a small miracle when the position of the sun, adequate weather conditions, and your eyes – otherwise focused on your busy life – align to create a rainbow. This may allow you to pause to celebrate the fleeting moment of trajectories meeting up. It is like nature offering a surprise party, while allowing us the pleasure of being a co-host.’ – Olafur Eliasson

‘Your light spectrum and presence’, a solo exhibition by Olafur Eliasson, now on view at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff White

https://vimeo.com/670635416

Olafur Eliasson's latest solo exhibition ‘Navegación situada’, now on view at Galería Elvira González in Madrid.

Now open at Galería Elvira González in Madrid, Olafur Eliasson's solo exhibition 'Navegación situada' explores how we navigate today's complex world through a series of works that delve into our sense of presence and invite the viewer to contemplate unexpected and open terrain.

On view through 2 April, the exhibition features a series of watercolours, hanging compasses, a large projection work, and a wall-based work of glass and driftwood.

‘The missing left brain’, 2022. On view now at Galería Elvira González in Madrid as part of Olafur’s latest solo exhibition ‘Navegación situada’.

‘In “Navegación situada”, I hope to place our sense of place and of being present under loving scrutiny. Walter D. Mignolo, an Argentinian literary theorist and specialist on decolonial theory, rephrased the Cartesian “I think therefore I am as I am where I do and think.” This is such a radical shift from what I have been brought up on. Thinking, doing, and place are fundamentally entangled. Being conscious of where I am is the first step to knowing who I am and to addressing fundamental questions of existence. But knowledge can only ever partial. The feminist and biologist Donna Haraway, whose work I admire, talks about “situated knowledges”: knowledges – in the plural – that are embodied and arise through your entanglement with a particular site, in a particular culture, and at a particular time. This is something I’ve only recently begun to recognise properly although I’ve long worked with the idea that “vision”, for instance, is embodied and particular, and that our entire sensorium facilitates how we connect with our specific surroundings and what we experience as our surroundings.’ – Olafur Eliasson on his exhibition ‘Navegación situada’ at Galería Elvira González, Madrid

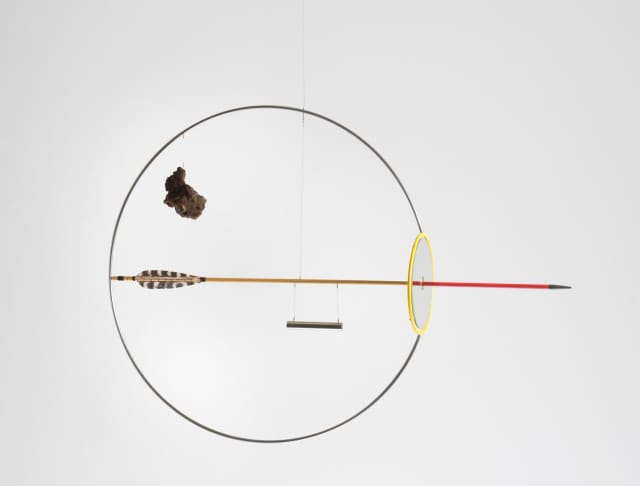

'Compass travellers (north)', 2022. Part of Olafur Eliasson's latest solo exhibition 'Navegación situada' at Galería Elvira González in Madrid, opening 20 January.

‘The round corner’, 2018. Photo: Jens Ziehe

'Your watercolour machine’, 2009

‘Your natural denudation inverted’, 1999. At the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, USA, a shallow pond was constructed around the trees in the courtyard. A plume of steam, channeled directly from the museum's heating system located in the adjacent building, was continuously emitted from the center of the pond.

‘Spatial orbit’, 2021. Photo: Jens Ziehe

‘Your invisible house’, 2005

‘The everyday life of the unforeseen’, 2021

‘Not-yet-conceived flare from a nearby, more-than-human future’, 2021. Photo credit: Jens Ziehe

Olafur Eliasson and Kumi Naidoo – On Art and Activism

On the occasion of COP 26 in Glasgow, Olafur Eliasson and Kumi Naidoo discuss if art and activism can learn from each other.

Kumi Naidoo is an activist and former Secretary-General of Amnesty International and former Executive Director of Greenpeace. He is currently a Bosch Academy Fellow and a Global Ambassador for Africans Rising for Justice, Peace and Dignity.

COP 26 in Glasgow is a definitive moment for heads of state, global leaders, and their teams to make binding decisions to significantly slow down the effects of climate change. Our actions today will shape the course of the next decade and beyond. It is an important opportunity to ask ourselves and one another: how can we work collaboratively across disciplines and geographic, cultural, and national borders, and in a manner that takes into account the needs of multiple generations and of all species, in order to navigate towards a safe and more just future? The climate crisis is a collective action problem – there is no one way to tackle this.

Together they discuss, in the face of the climate crisis, how can the work of artists help create change? And what can activism achieve – can it be done differently?

People in the crowd illuminate Little Sun torches during the Pathway to Paris event at the Theatre Royal during COP26, this year's UN climate change conference, in Glasgow. Photo: Roberto Ricciuti/Redferns

‘The presence of absence pavilion’, 2019. On view at Expo 2020 Dubai – the first world fair to be held in the Middle East – now through 31 March 2022.

‘Waterfall’, 2004, ARoS Art Museum, Denmark, 2004. Installed in both interior and exterior locations, the cascading waterfall evokes the sight, sounds, and rhythm of a natural waterfall. The clearly exposed construction allows viewers to understand the mechanism behind the phenomenon. Photo: Poul Pedersen

Future Assembly project logo, 2021. To learn more about the project, visit the dedicated website https://futureassembly.earth/.

The Venice Biennale Architettura 2021 asks, How will we live together?

Future Assembly is a response to curator Hashim Sarkis’s invitation to imagine a design inspired by the United Nations – the current paradigm for a multilateral assembly. We invited all Biennale participants to come together and offer more-than-human Stakeholders from their local situations for Future Assembly, in order to find novel, imaginative ways of spatially representing diverse, nonhuman agencies. More than 50 proposed new planetary representatives now make up the Assembly. Surrounding the central assembly, Future Assembly Chart forms a living collection of attempts by humans to recognise and secure the rights-of-nature.

We believe that our future imaginaries must include the more-than-human – that which both includes and exceeds humanity. The more-than-human is the many entanglements of human existence with living and nonliving entities, all of which have a stake in the planet’s future. The more-than-human means more than just nonhuman: It is the many overlapping spheres of human, nonhuman, living, and nonliving existence; it is as much a situation as any entity. One snapshot of the more-than-human could be the Sahara winds carrying desert sands high into the atmosphere and across the Atlantic, seeding the Amazon rainforest with vital nutrients that grow the ‘lungs of Earth’. Yet another could be the human decimation of the wolf population in Yellowstone, breaking a single link in the food chain and unleashing a cascade of effects that literally throws a whole river off course. The more-than-human is also the flipside – the reintroduction of that wolf species to the same park, transforming an entire habitat and even recalibrating its microclimate. The more-than-human challenges perceived boundaries of human identity and swells the definition of ‘we’.

Future Assembly is a response to Biennale curator Hashim Sarkis’s invitation to imagine a multilateral design, inspired by the United Nations, for his exhibition in the Central Pavilion. The United Nations – the paradigm for a multilateral assembly of the twentieth century – was founded in 1945 in response to political, social, economic, and humanitarian crises. Today, an equally radical response to the urgent, human-propelled climate crisis is needed.

Studio Other Spaces (SOS), represented by artist Olafur Eliasson and architect Sebastian Behmann, is collaborating especially for this occasion with Paola Antonelli, senior curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Hadeel Ibrahim, activist; Caroline A. Jones, professor of art history at MIT; Mariana Mazzucato, professor and founding director of the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose at University College London; Kumi Naidoo, ambassador for Africans Rising for Justice, Peace and Dignity; and Mary Robinson, chair of the Elders and adjunct professor of climate justice at Trinity College, Dublin. Future Assembly is structured around reciprocity, collaboration and coexistence. This extends to our design approach: Imagining possible futures requires us to stretch our definitions of co-existence and collaboration to include the more-than-human and to find novel ways of spatially representing diverse nonhuman agencies so they may take a seat at the table.