‘The current pandemic has caused immeasurable suffering and disrupted so much of our everyday existence together. This is especially true for those of us who value and take part in cultural life. Because many of the important cultural sites that we take for granted are all closed – cinemas, theatres, concert houses, clubs, museums and stadiums – the only public spaces where we can move about safely together is outdoors, in the shared space of the city. It’s important to celebrate – even now – that public space belongs to all of us and that it is, in fact, very valuable.’ – Olafur @Dazed

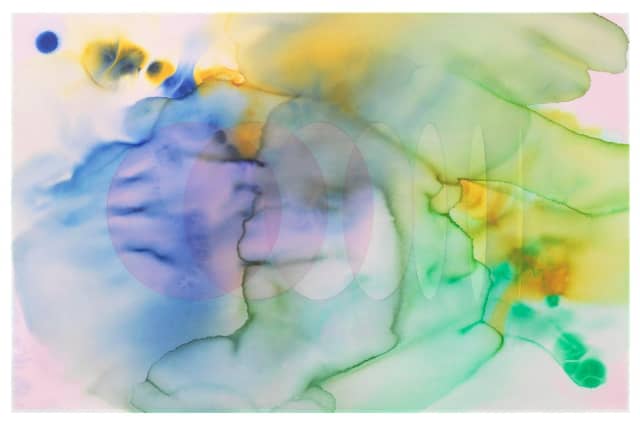

The exhibition ‘Unreal City’ is on now through 5 January. It features 36 digital sculptures arranged as a walking tour along the River Thames, including Olafur Eliasson’s artwork ‘WUNDERKAMMER’, 2020. The sculptures, created to be experienced in AR using Apple’s ARKit, are arranged across 24 sites between Waterloo Bridge and Millennium Bridge on the Southbank. Organized by Acute Art and Dazed Media, featuring works by Olafur Eliasson, Cao Fei, Alicja Kwade, Koo Jeong A, Marco Brambilla, Darren Bader, KAWS, Bjarne Melgaard, and Tomás Saraceno.

To view the exhibition, download the free Acute Art app on your device to get the map and view the artworks.

https://acuteart.com/