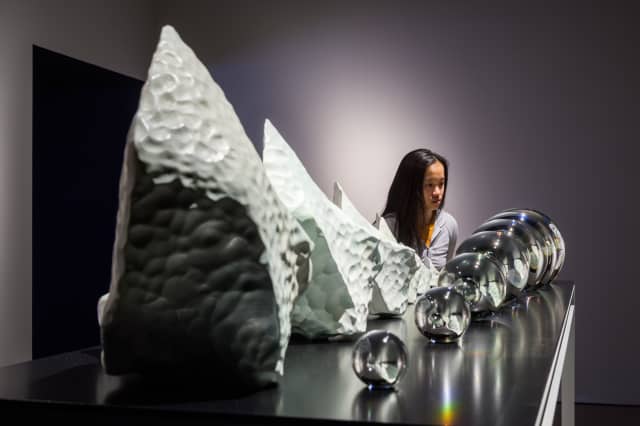

Seven bronze sculptures representing a block of ice as it melts are arranged from largest to smallest on a high, black display table. Next to each is a transparent glass sphere. The size of each sphere corresponds to the volume of water that has metaphorically disappeared from the bronze ice. The spheres increase in size in inverse relation to the shrinking of the ice. The largest of the ice blocks is based on scans of pieces of ice that Eliasson and his team collected from a beach on the southern coast of Iceland known as Diamond Beach. Glistening pieces of ice wash up there after breaking off the Breithamerkurjökull glacier and remain on shore until they melt away. In 2020, Eliasson and his team made 3D scans of individual ice fragments in order to capture the ephemeral forms before they disappeared for ever; the data can be used to replicate the ice in a variety of materials. The six smaller ice fragments were extrapolated digitally from the original scan. Software was used to simulate the complex process of melting, to predict where the block might lose mass and at what rate. Moulds were made from the digital files, and the bronze forms were cast according to traditional methods in a hybrid technique that unites timeless knowhow with modern technology. The material has been treated with a whitish, matte patina that references obliquely the whiteness of the ice that inspired it. Bronze, a favourite material of sculptors since antiquity, was chosen because of its association with permanence and commemoration. Using the metal to immortalise these ephemeral, disappearing forms produces a kind of temporal incongruity. Time is also present in the number of blocks and glass spheres: seven for the seven days of the week. And time is of the essence in our struggle to slow down climate change and protect the glaciers.

| Artwork details | |

Title |

The last seven days of glacial ice |

Year |

2024 |

Materials |

Bronze casts (with white patina, and wax), glass spheres, stainless steel, aluminium, paint (grey, black) |